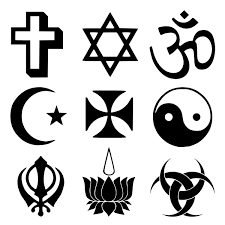

Words are important and “religion” is a central word

in our conversation. Religion is an extremely complex word with a complex

history. Its modern usage as a reference to a set of beliefs and rituals to

provide access to God begins really with the 17th century but the

origins of the word go back much earlier to the Romans. Even there, the usage

is complex. For the Roman Empire, religion (religio)

was what bound all the people together with the gods. In that, the Emperor, as summus pontifex (highest bridge builder,

high priest) played a central role. For the Christians of the first three

centuries to refer to their Way as religion would have been the height of

blasphemy. The word never appears in the New Testament though the backdrop of

religion as practiced by the Roman Empire is quite present. It was only after

Constantine that Christians saw themselves as having a religion with the Pope

as summus pontifex. In other words,

the religion of the Empire was supplanted by the Christian religion. Basilicas

were built, people were converted massively and Christianity became the

established state religion and thus a major institution with considerable power

in the Empire of the time. Outreach to the pagans led at this point to some

pretty violent proceedings.

When I settled in Peru in 1980, Catholicism was the

established state religion there. During my time there, a concordat was signed

between the governments of Peru and the Vatican. At the same time, the Catholic

Church was disestablished, although with privileges. During the time of

Duplessis, in Quebec during the 1940s and 1950s, the Catholic Church was the

established Church, at least in practice. The connection between “religion” and

the state continues, then, right into our own day and with very significant

impact for those who belong to a major Church. Moreover, this is not limited to

Christianity. In Myanmar, Buddhism is protected by the State, with dire

consequences for the Rohingyas. In India, Hinduism is protected and Islam can

more properly be called an established religion in Indonesia, Bangladesh and

Pakistan.

So, evoking the word “religion” is unavoidably linked

to a question of privilege and establishment. I mentioned that the modern definition

of religion really dates from the 17th century. This is the time of

colonization. It cannot be said enough that Hindus, Buddhists, Shintoists and

Confucians – we often forget about these latter in China – would not normally

identify themselves as following a religion. Religion was a term imposed on

them by colonizing powers in order to provide a framework for control and,

often, repression. Hindi, in India, has no precise word corresponding to

religion.

For the West, “religion” means an institutionalized

set of beliefs and practices that has hierarchies of power and decision-making,

that has rituals of initiation and communion with the divine, that has beliefs

and disciplines and that can be controlled, managed. This institutionalized

dimension of religion has important implications when it comes to determining

how to relate to those outside its circle. The document in Vatican II on

religious liberty, largely written by John Courtney Murray and inspired by the

experience of the United States, marked a turning point in relations with

Protestants in particular. This document

was part of the final push of the Council to address also the question of Jews

and of non-Christian “religions.”

On the other hand, at least today, “religion” clearly

also refers to a very personal and cultural phenomenon of entering into

communication and communion with the Other, with the Transcendent, who gives

meaning and direction to the lives of those who belong to a specific circle. In

the Abrahamic tradition it is a journey through life rooted in a covenant. In

this sense it is a call to interiority, to an asceticism of life and a moral

journey as well. Thomas Aquinas, already

in the 13th century, defined religion as a virtue of devotion to and

service of God.

Of all the world “religions,” Christianity, and in

particular, the Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox Churches represent the most

institutionalized expressions of religion.

The Indigenous path is one of connection and communication

with the divine, clearly outside institutional parameters. I don’t know of any

Indigenous culture that identifies itself as “religious.” They see their ways

as “spiritual,” much like Hindus and Buddhists might.

All of this raises a question about whom we are

referring to and what is the ground we stand on when we ask about the place of

world “religions” in Catholic theology.

It would be nice if we could just agree on a proper

definition for our purposes and then proceed. It would be nice if we could say

that we are going to talk just about the “spiritual” dimension of our various

traditions and leave aside the rest. It would also be tempting to just deal

with the institutional differences. But, it is not so simple. The institutional

dimensions, the belief and ritual systems and the spiritual journey are

intimately intertwined in all dimensions in the existence of all these various

traditions. We will constantly need to remind ourselves of the distinctions and

variations of meaning we assign both to our own traditions and to that of others.

We need to use the word “religion” with respect for its complexity.

Finally, I would like to suggest, as a working

principle, that the institutional dimension of religion is ultimately intended

(although not always effective) as a support and guidance for the pathway or

spiritual journey dimension of religion. This may be an important distinction

for us as we proceed.

I suggest that we agree to swallow the complexity and

try to be a clear as we can about what we are talking about at every stage. For

example, when we say with the Catholic Church that “outside the Church there is

no salvation,” we need to be clear about what dimension of religion we are

talking about. When we, as Catholics says, that God wills the salvation of all

humanity, indeed of all creation and that Jesus died for all, we need to be

very careful how we frame this in the light of the documents of Vatican II.

When we say, as some still do, that “pagan” practices are superstitions and

idolatry, we need to be very clear about what we are saying and its implication

of exclusion.

Augustine spoke of two sources of revelation, of God’s

communication of self to us: the book of creation and the book of the

scriptures. We who belong to the monotheistic religions (Jews, Christians,

Muslims) are often called “peoples of the book.”

Of course, we are more conscious today that the book

of the scriptures is set within the book of creation since human words, events

and writing are all part of God’s creation. In the scriptures we find God

speaking through events of nature: volcanic eruptions, floods, parting waters,

famine and disease, storms on the sea, sowing the seed and reaping the harvest,

through political events like battles and voyages, through dreams. These are

often set in the form of stories and parables. There are also rituals that

evoke and commemorate all these events. Moreover, at times, certain prophets

proclaim the word of God as a warning to the people who have wandered from the

covenant that God has proclaimed between himself and them. In fact, God never

speaks outside the context of creation; it is through the natural that God

reveals the Word.

From the viewpoint of the receiver of the word, there

is therefore the natural events of life, whether something extraordinary like a

battle or bread falling from the skies or something quite ordinary like seeing

a broken jar lying at the side of the road. This natural moment takes on a

special character for the person who is attentive in faith to God’s speaking

and, through the encounter, reveals a deeper dimension that speaks God’s word.

Jeremiah raises the question whether one can always be confident of the word

that is spoken. When it is God who speaks we can be certain but since we are

imperfect hearers, we can doubt. The doubt is not whether God speaks but

whether we have listened correctly.

The fact that God speaks through the events of our

lives, means that God always speaks from within the limitations of human

perception and language. God however is not limited. God is totally other. Yet

God limits himself to our framework of communication. Moreover, we have no way

to speak of our experience of God’s revelation except through the context of

creation, of human language. Because God’s word is mysterious (utterly filled

with light to the point of blinding us), we are aware that our attempts to

express it fall short. The most adequate human language for expressing God’s

word is analogy expressed in ritual, story, analogy. This sort of language

leaves open the possibility of discovering deeper understanding. This is true

of God’s word as embodied in the scriptures and also of the doctrines, rituals

and wisdom shared today in our faith communities. Speculative theology attempts

to draw out a rational understanding of doctrines but can never replace the

analogies which ground them.

All of this will become significant when we come to

the incarnation of the Word in Jesus and the elevation of Jesus as Christ the

Lord after the resurrection.

Historically the Christological doctrine developed

before that of the Trinity. The doctrine of the Trinity wasn’t entirely

complete before around the 8th century. Ultimately, the emphasis

here is on the unicity of God and the distinction between Father and Son.

First of all, Christianity, along with Judaism and

Islam, is a monotheistic religion at least in Christian eyes. The Jews of

course have great difficulty with the divinity of Christ. They see this as

creating two gods. Islam also has difficulty seeing Christianity as

monotheistic. It is extremely important, in today’s world, for us to continue

to insist that God is One. There is only one God.

Therefore, when we speak of Trinity, we are talking of

a reality that is interior to one God and in no way divisive of the unicity of

God. The Father is God, the Son is God, the Holy Spirit is God. But, there is

only one God. More than that, it is a doctrine of the Catholic Church that all

actions God directs to the exterior (creation in particular and also

salvation/liberation) are actions of all three persons of the Trinity. This is

the doctrine. And already it is full of analogies: Father, Son, Spirit.

Doctrines posit statements of faith, not theology. Almost always they are rooted in analogies.

Analogies are always somewhat ambiguous: they are and are not entirely

representations of the reality. The Father is father, but not quite like your

or my father. The Son is son but not quite like you or I are sons. God is one

and three but the references to numbers is also analogous since we are speaking

of the divine, who manages to embody and escape all that.

Again, doctrines do not posit any explanation. They

are statements of faith. The Church never endorses a particular theology - other

than to say, Nihil Obstat. The

doctrine about Christ says that Jesus incarnates the Second Person of the

Trinity, or more accurately, is the only begotten Son of God. The doctrine says

that there are three persons in one God. These are doctrinal statements of

faith, not systematic theology. When Bernard Lonergan speaks of a stage of

theology called doctrine, he is pointing to the effort to determine exactly

what the Church has said and how and when. This is different from systematic

theology, which offers rational explanations to help us understand those

doctrinal statements of faith. In some way, I suppose it could be said that

doctrine operates on the basis of truth and systematic theology on the basis of

verified hypotheses: Does it adequately explain the doctrine?

The Church has stated, over time, that the Trinity is

made up of three persons: Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. However, right

from the start we are back to analogy. There are several words here that must

be taken analogically and not literally. They are called persons. But, they are

not quite persons like human persons. There is an analogy, but there are also

differences. I don’t want to go into any precise descriptions of the difference

between the two. Surely, we don’t think that the Father became so in begetting the

Son in the same way my father begot me! It is an analogy. Yet it is not a

metaphor. There is some real semblance between what is the normal usage of the

word and this, its analogical usage. The same is true for the Holy Spirit. And,

the whole traditional theology of the trinity, derived largely from Athanasius,

is a piece of systematic theology that helps us (in the best of cases)

understand how it could be that one God is, in some respect, three. I should

add that, in order to explain the internal nature of the three persons of the

Trinity, the basic reference is not so much to family as to the generation of

Word and Love. We can come back to that later.

I do not question either the doctrine (dogma in fact)

or the theology. But, I do want to point out the distinction between a

statement of doctrine and a theological explanation of that statement.

The distinction between doctrine and theology is true

also of the incarnation. We say that Jesus is one person (a divine person in

fact, the Son of the Father, the Word of God) with two natures (Council of

Calcedon). This is doctrine and it is full of analogous terms: person, son

word, nature. However, the explanation of how this works is a matter for

speculative theology. The doctrine of Nicea (that Jesus is divine) is a

statement of faith; the theology is not. The series of analogies - son, word,

person, nature - are taken from human experience, stated in the doctrine and

then given a theological explanation subsequently. The theological explanation

is not a matter of faith but an attempt to help us understand the doctrine,

which is a requirement.

Jesus is the incarnate Word of God, the second person

of the Trinity. This is who he is as a person. He is not a human person; he is

a divine person with two natures.

So, then, we come to the suffering, death and

resurrection of Jesus. Who suffered, died and rose? Jesus died. Did God die? Jesus died and rose. Jesus who was both divine

(by nature) and human (by nature). However, Jesus could only die in his human

nature. It is not in the nature of God, the second (or any) person of the Trinity

to die – or rise again. Jesus, the divine person died as human but not as

divine.

This is similar to the explanation of the

consciousness of Christ in Bernard Lonergan’s Christology. Jesus was a divine

person (ens, being) with two natures.

Did Jesus then know everything that God knows? Yes, as a divine person (ens) but not in his human nature. In

that he was like every other human being who had to learn. So, God died on the

Cross, as Mary can claim to be Mother of God. God died on the cross in the

human nature of Jesus. But the distinctions still have to be maintained. God

did not die as God but as human in Jesus. There is only one ens or being: that of God.

Jesus died for the salvation/liberation of the whole

world, all peoples – according to the writings of Paul and confirmed by Church

teaching throughout its history. But the salvation/liberation of the whole

world could take place not because of the human nature of Jesus but because of

the union of that human nature with the divine nature of the person who is the

Word in the Trinity. Moreover, that divine nature does not suffer the same

limitation as the human nature of Jesus. The power of the Word is divine,

extensive and enduring.

The final step is to consider what Christology might

mean for a statement that affirms the traditional doctrine that Jesus died and

rose to save all mankind and that it is only through the church (the community

of believers) that we can be “saved” while going on to say that the divine Word

through the agency of the Holy Spirit can inspire men and women who have not

been baptized. (By the way, the wording of a theology, or of a doctrinal

statement, is obviously limited to the capacity of human language. That is why

analogy is so helpful because it points, in some way, beyond the words. Our

faith is faith in someone, in the Word, not words.)

You will remember that when Peter went to visit the

home of Cornelius, he encountered a group of people on whom the Spirit of God

fell as in Pentecost (Acts 10. See also Peter’s vision and visit in Acts 11).

This was before Peter baptized them.

Thus, the Spirit works in us before baptism, that is before our formal entry

into the Church. We are made holy before baptism while technically still

outside the Church. In adult catechumens, faith is present before baptism.

Thus, the statement that we cannot be saved outside the church/Church, needs to

be somewhat qualified. God does give faith before entry into the Church. Obviously

in this case, the process led to affirmation of faith in Christ. But, the

principle remains that baptism is not a sine

qua non for the saving action of God.

Jesus, who died on the cross is also the Divine Word

whose action extends throughout all creation with God’s own freedom to act.

While, in his human nature, Jesus saving act is limited to those whom he is

able to reach through direct contact, the same is not true of his divine

nature.

It is clear from John that the key criterion for

recognizing the presence of God’s Spirit at work is agape (love). (Ubi caritas et amor, Deus ibi est.) We

know that billions of people throughout the world and throughout history have

lived exemplary lives, filled with self-sacrificing love that cannot be named

other than being lives of agape.

Agape is the work of the Holy Spirit; it is the work of the Trinity; it is the

primary sign and core reality of living in the saving grace of the Risen

Christ.

We also know that for many – the majority – of these

people, the motivating factor in their life of agape has been their

participation in religious traditions of their culture: Hindu, Islam, Buddhist,

Indigenous or other. These systems of belief and ritual have nourished them in

developing lives of agape. It seems to me not too broad a leap to affirm that

these traditions have been paths to agape

for them, paths leading them to God. God is love, God is agape. The church, the community of believers, the mystical body of

Christ can be found wherever agape is

found.

God established a covenant with Adam and Noah, then

with Abraham, then with Moses and further on with David. Finally, we have the

New Covenant offered us in Jesus. When God establishes a covenant, as the

people slowly learned, God never retires it; it is an everlasting covenant.

This is true for Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses and David. Those covenants remain.

“I have not come to abolish the Law…” It is true for the covenant offered

through Jesus. The question, for me, at this point is also whether there could

be further covenants. God might establish a covenant with peoples in Africa,

Asia, Latin America. Where would Jesus fit in?

I am speaking from a Christian perspective. I am

trying to understand their experience out of my own tradition and put words to

it. I am attempting a speculative theology based in part on the doctrines of

Catholicism and the challenges of a grasp of the history and contemporary

situation of humanity. I am trying, in the spirit of Gaudium et spes from the Second Vatican Council, to discern the

Signs of the Times, the ways in which the Spirit of God moves not just in the

Church but throughout the world.

My suggestion is that God indeed could and does act in

shaping and inspiring traditions other than Christian and not just as a stopgap

measure before everyone joins the Church. (After 2000 years, I think it fairly

safe to say that a world in which everyone was Catholic is highly improbable, without

prejudice to what may happen at the Parousia. I would argue that God works primarily in the

“world” (God’s nascent and largely hidden kingdom) and that it is largely the

role of the Church to bear witness to that transforming action.

All the covenants (including those with non-Christian

religions) go in the same direction and issue from the same source. They are

all covenants of fidelity and of agape.

And it is hard for me to believe, based on the words of scripture, that God

withholds that offer of covenant to anyone, to any people, ever, anywhere.

In some way I guess my position is somewhat akin to

that of Karl Rahner though I don’t like the phrase “anonymous Christian.” I

find it patronizing and colonializing. Nevertheless, that God, the Word of God,

the Spirit of God, is free to work outside the framework of our Catholic

institution and doctrinal framework seems to me unavoidable.

If I am even close to having a slight grasp of truth

here, I believe the challenge is enormous for Christians to rethink their whole

place in God’s scheme of things. I have no doubt, as a Catholic, in saying that

Jesus died for all and that Jesus calls us, above all, to a life of agape such as he himself lived it. But,

I am adding that that life of agape

is available beyond the boundaries of what we know as the Roman Catholic Church

or even of those baptized as Christians. And I am saying that other religious

traditions can be, for at least some who live within the framework of those

traditions, paths to God. I am saying that the mystical body of Christ is present

throughout time and in all nations and religious traditions and that we should

be careful not to tread too heavily on Christ’s body.

There an interesting collection of contributions in

this sense from representatives from about twenty traditions in a book entitled

Toward a Global Theology. The

question asked of each contributor was: Do you think it is possible to have a

common theology? In other words, can we speak of the same God and say something

together. I think it is generally much easier for those outside the Christian

tradition to accept that our Christian tradition is a way to God than for us to

accept theirs.

I have an interesting collection of

contributions in this sense from representatives from about twenty traditions

in a book entitled Toward a Global Theology that my little Dunamis Publications

put out about 10 years ago. I have a whole box of them in my closet!